Cape Horn on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

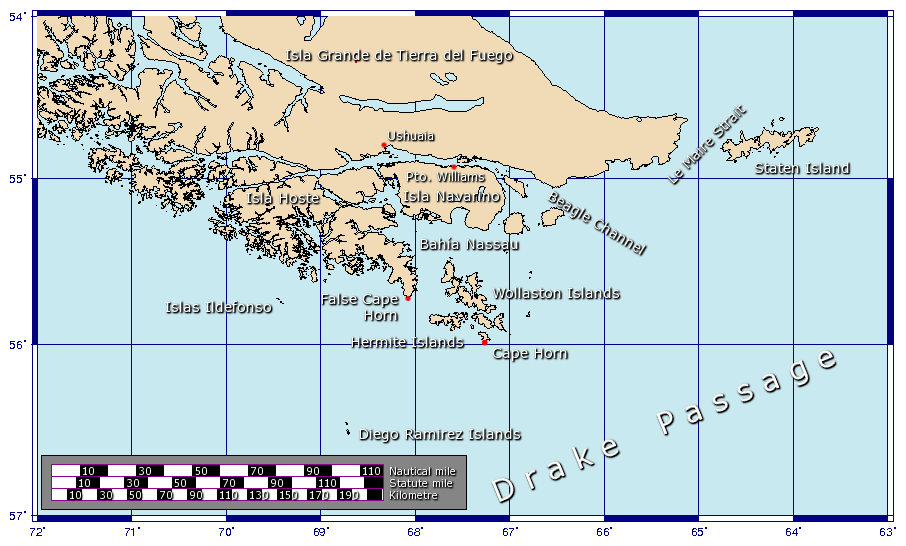

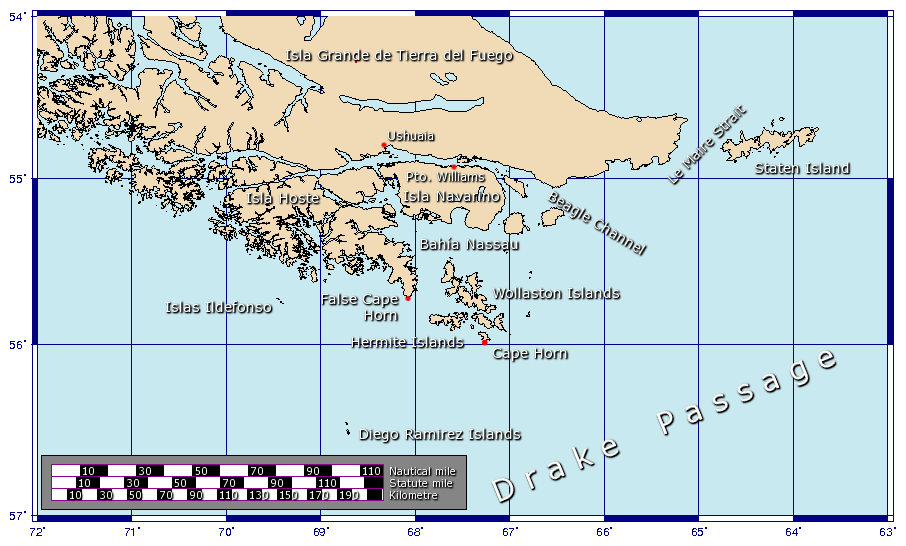

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the

Cape Horn is located on

Cape Horn is located on

, by Paolo Venanzangeli; from Nautical Web. Retrieved February 5, 2006. It marks the north edge of the

Cape Horn is part of the

Cape Horn is part of the

, by P.J. Gladnick; from eSsortment, 2002. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

Several factors combine to make the passage around Cape Horn one of the most hazardous shipping routes in the world: the fierce sailing conditions prevalent in the Southern Ocean generally; the geography of the passage south of the Horn; and the extreme southern latitude of the Horn, at 56° south. (For comparison,

Several factors combine to make the passage around Cape Horn one of the most hazardous shipping routes in the world: the fierce sailing conditions prevalent in the Southern Ocean generally; the geography of the passage south of the Horn; and the extreme southern latitude of the Horn, at 56° south. (For comparison,

Cape Horn lighthouse

. However, the Chilean Navy station, including the lighthouse ( ARLS CHI-030, ) and the memorial, are not located on Cape Horn (which is difficult to access either by land or sea), but on another land point about one mile east-northeast. On Cape Horn proper is a smaller fiberglass light tower, with a focal plane of and a range of about . This is the authentic Cape Horn lighthouse ( ARLS CHI-006, ), and as such the world's southernmost traditional lighthouse. A few minor

Despite the opening of the

Despite the opening of the

In 1526 the Spanish vessel the ''San Lesmes'' commanded by

In 1526 the Spanish vessel the ''San Lesmes'' commanded by

From the 18th to the early 20th centuries, Cape Horn was a part of the clipper routes which carried much of the world's trade.

From the 18th to the early 20th centuries, Cape Horn was a part of the clipper routes which carried much of the world's trade.

Guide: How to visit Cape Horn

International Association of Cape Horners

Chilean Brotherhood of Cape Horn Captains (Caphorniers)

– Chilean sculptor José Balcells' article (Spanish)

Robert FitzRoy's commemorative plaque in Horn Island (image)

– antique charts of the Cape Horn region

–

Satellite image and infopoints

on BlooSee {{Authority control Extreme points of Earth Landforms of Magallanes Region

Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

of southern Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, and is located on the small Hornos Island

Hornos Island ( es, Isla Hornos) is a Chilean island at the southern tip of South America. The island is mostly known for being the location of Cape Horn. It is generally considered South America's southernmost island, but the Diego Ramírez Islan ...

. Although not the most southerly point of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

(which are the Diego Ramírez Islands

The Diego Ramírez Islands ( es, Islas Diego Ramírez) are a small group of subantarctic islands located in the southernmost extreme of Chile.

History

The islands were first sighted on 12 February 1619 by the Spanish Garcia de Nodal expedition, ...

), Cape Horn marks the northern boundary of the Drake Passage

The Drake Passage (referred to as Mar de Hoces Hoces Sea"in Spanish-speaking countries) is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atla ...

and marks where the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans meet.

Cape Horn was identified by mariners and first rounded in 1616 by the Dutchman Willem Schouten

Willem Cornelisz Schouten ( – 1625) was a Dutch navigator for the Dutch East India Company. He was the first to sail the Cape Horn route to the Pacific Ocean.

Biography

Willem Cornelisz Schouten was born in c. 1567 in Hoorn, Holland, Seve ...

and Jacob Le Maire

Jacob Le Maire (c. 1585 – 22 December 1616) was a Dutch mariner who circumnavigated the earth in 1615 and 1616. The strait between Tierra del Fuego and Isla de los Estados was named the Le Maire Strait in his honour, though not without controver ...

, who named it after the city of Hoorn in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

. For decades, Cape Horn was a major milestone on the clipper route

The clipper route was the traditional route derived from the Brouwer Route and sailed by clipper ships between Europe and the Far East, Australia and New Zealand. The route ran from west to east through the Southern Ocean, to make use of the s ...

, by which sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships c ...

s carried trade around the world. The waters around Cape Horn are particularly hazardous, owing to strong winds, large waves, strong currents and iceberg

An iceberg is a piece of freshwater ice more than 15 m long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open (salt) water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially-derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". The ...

s.

The need for boats and ships to round Cape Horn was greatly reduced by the opening of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

in August 1914. Sailing around Cape Horn is still widely regarded as one of the major challenges in yachting

Yachting is the use of recreational boats and ships called ''yachts'' for racing or cruising. Yachts are distinguished from working ships mainly by their leisure purpose. "Yacht" derives from the Dutch word '' jacht'' ("hunt"). With sailboats, ...

. Thus, a few recreational sailors continue to sail this route, sometimes as part of a circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical object, astronomical body (e.g. a planet or natural satellite, moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circ ...

of the globe. Almost all of these choose routes through the channels to the north of the Cape. (Many take a detour through the islands and anchor to wait for fair weather to visit Horn Island, or sail around it to replicate a rounding of this historic point.) Several prominent ocean yacht races, notably the Volvo Ocean Race

The Ocean Race is a yacht race around the world, held every three or four years since 1973. Originally named the Whitbread Round the World Race after its initiating sponsor, British brewing company Whitbread, in 2001 it became the Volvo Ocean Ra ...

, Velux 5 Oceans Race The Velux 5 Oceans Race was a round-the-world single-handed yacht race, sailed in stages, managed by Clipper Ventures since 2000. Its most recent name comes from its main sponsor Velux. Originally known as the BOC Challenge, for the title sponsor ...

, and the solo Vendée Globe

-->

The Vendée Globe is a single-handed (solo) non-stop round the world yacht race. The race was founded by Philippe Jeantot in 1989, and since 1992 has taken place every four years. It is named after the Département of Vendée, in France ...

and Golden Globe Race

The ''Sunday Times'' Golden Globe Race was a non-stop, single-handed sailing, single-handed, circumnavigation, round-the-world yacht racing, yacht race, held in 1968–1969, and was the first round-the-world yacht race. The race was controversi ...

, sail around the world via the Horn. Speed records for round-the-world sailing are recognized for following this route.

Geography and ecology

Hornos Island

Hornos Island ( es, Isla Hornos) is a Chilean island at the southern tip of South America. The island is mostly known for being the location of Cape Horn. It is generally considered South America's southernmost island, but the Diego Ramírez Islan ...

in the Hermite Islands

__NOTOC__

The Hermite Islands () are the islands ''Hermite'', ''Herschel'', ''Deceit'' and ''Hornos'' as well as the islets ''Maxwell'', ''Jerdán'', ''Arrecife'', ''Chanticleer'', ''Hall'', ''Deceit (islet)'', and ''Hasse'' at almost the southe ...

group, at the southern end of the Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

.''Cape Horn the Terrible'', by Paolo Venanzangeli; from Nautical Web. Retrieved February 5, 2006. It marks the north edge of the

Drake Passage

The Drake Passage (referred to as Mar de Hoces Hoces Sea"in Spanish-speaking countries) is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atla ...

, the strait

A strait is an oceanic landform connecting two seas or two other large areas of water. The surface water generally flows at the same elevation on both sides and through the strait in either direction. Most commonly, it is a narrow ocean channe ...

between South America and Antarctica. It is located in Cabo de Hornos National Park

Cabo de Hornos National Park is a protected area in southern Chile that was designated a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO in 2005, along with Alberto de Agostini National Park. The world's southernmost national park, it is located 12 hours by boat from ...

.

The cape lies within Chilean territorial waters, and the Chilean Navy maintains a station on Hoorn Island, consisting of a residence, utility building, chapel, and lighthouse. A short distance from the main station is a memorial, including a large sculpture made by Chilean sculptor ''José Balcells'' featuring the silhouette of an albatross, in remembrance of the sailors who died while attempting to "round the Horn". It was erected in 1992 through the initiative of the Chilean Section of the Cape Horn Captains Brotherhood. Due to severe winds characteristic of the region, the sculpture was blown over in 2014. A 2019 research expedition found the world's southernmost tree growing, a Magellan's beech mostly bent to the ground, on a northeast-facing slope at the island's southeast corner. Cape Horn is the southern limit of the range of the Magellanic penguin

The Magellanic penguin (''Spheniscus magellanicus'') is a South American penguin, breeding in coastal Patagonia, including Argentina, Chile, and the Falkland Islands, with some migrating to Brazil and Uruguay, where they are occasionally seen a ...

.

Climate

The climate in the region is generally cool, owing to the southern latitude. There are no weather stations in the group of islands including Cape Horn; but a study in 1882–1883, found an annual rainfall of , with an average annual temperature of . Winds were reported to average , (5 Bf), with squalls of over , (10 Bf) occurring in all seasons. There are 278 days of rainfall (70 days snow) and of annual rainfall Cloud coverage is generally extensive, with averages from 5.2 eighths in May and July to 6.4 eighths in December and January. Precipitation is high throughout the year: the weather station on the nearbyDiego Ramírez Islands

The Diego Ramírez Islands ( es, Islas Diego Ramírez) are a small group of subantarctic islands located in the southernmost extreme of Chile.

History

The islands were first sighted on 12 February 1619 by the Spanish Garcia de Nodal expedition, ...

, 109 kilometres (68 mi) south-west in the Drake Passage

The Drake Passage (referred to as Mar de Hoces Hoces Sea"in Spanish-speaking countries) is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atla ...

, shows the greatest rainfall in March, averaging 137.4 millimetres (5.41 in); while October, which has the least rainfall, still averages 93.7 millimetres (3.69 in). Wind conditions are generally severe, particularly in winter. In summer, the wind at Cape Horn is gale

A gale is a strong wind; the word is typically used as a descriptor in nautical contexts. The U.S. National Weather Service defines a gale as sustained surface winds moving at a speed of between 34 and 47 knots (, or ).Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

wrote: "One sight of such a coast is enough to make a landsman dream for a week about shipwrecks, peril and death."

Being the southernmost point of land outside of Antarctica, the region experiences barely 7 hours of daylight during the June solstice, with Cape Horn itself having 6 hours and 57 minutes. The region experiences around 17 and a half hours of daylight during the December solstice, and experiences only nautical twilight

Twilight is light produced by sunlight scattering in the upper atmosphere, when the Sun is below the horizon, which illuminates the lower atmosphere and the Earth's surface. The word twilight can also refer to the periods of time when this il ...

from civil dusk to civil dawn. White nights

White night, White Night, or White Nights may refer to:

* White night (astronomy), a night in which it never gets completely dark, at high latitudes outside the Arctic and Antarctic Circles

* White Night festivals, all-night arts festivals held ...

occur during the week around the December solstice.

Cape Horn yields a subpolar oceanic climate

An oceanic climate, also known as a marine climate, is the humid temperate climate sub-type in Köppen classification ''Cfb'', typical of west coasts in higher middle latitudes of continents, generally featuring cool summers and mild winters ...

('' Cfb''), with abundant precipitation—much of which falls as sleet and snow.

Political

Cape Horn is part of the

Cape Horn is part of the Commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

Administrative-territorial entities

* Commune (administrative division), a municipality or township

** Communes of ...

of Cabo de Hornos

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

, whose capital is Puerto Williams

Puerto Williams (; Spanish for "Port Williams") is the city, port and naval base on Navarino Island in Chile. It faces the Beagle Channel. It is the capital of the Chilean Antarctic Province, one of four provinces in the Magellan and Chilean An ...

; this in turn is part of Antártica Chilena Province, whose capital is also Puerto Williams. The area is part of the Magallanes y la Antártica Chilena Region

Magallanes may refer to:

* Ferdinand Magellan (1480–1521), Portuguese explorer who led part of the first expedition around the world

* Strait of Magellan, the strait between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, located in Chile

Places

* Magallanes ...

of Chile. Puerto Toro

Puerto Toro is a hamlet on the eastern coast of Navarino Island, Chile. Puerto Toro was founded in 1892 during the Tierra del Fuego Gold Rush by Governor of Punta Arenas Señoret.Bascopé Julio, JoaquínSENTIDOS COLONIALES I. EL ORO Y LA VIDA SALVA ...

, a few miles south of Puerto Williams, is the closest town to the cape.

Modern navigation

Many modern tankers are too wide to fit through the Panama Canal, as are a few passenger ships and several aircraft carriers. But there are no regular commercial routes around the Horn, and modern ships carrying cargo are rarely seen. However, a number ofcruise ship

Cruise ships are large passenger ships used mainly for vacationing. Unlike ocean liners, which are used for transport, cruise ships typically embark on round-trip voyages to various ports-of-call, where passengers may go on tours known as "s ...

s routinely round the Horn when traveling from one ocean to the other. These often stop in Ushuaia or Punta Arenas

Punta Arenas (; historically Sandy Point in English) is the capital city of Chile's southernmost region, Magallanes and Antarctica Chilena. The city was officially renamed as Magallanes in 1927, but in 1938 it was changed back to "Punta Are ...

as well as Port Stanley. Some of the small passenger vessels shuttling between Ushuaia and the Antarctic Peninsula will pass the Horn too, time and weather permitting.

Sailing routes

A number of potential sailing routes may be followed around the tip of South America. TheStrait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural pass ...

, between the mainland and Tierra del Fuego, is a major—although narrow—passage, which was in use for trade well before the Horn was discovered. The Beagle Channel

Beagle Channel (; Yahgan: ''Onašaga'') is a strait in the Tierra del Fuego Archipelago, on the extreme southern tip of South America between Chile and Argentina. The channel separates the larger main island of Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego f ...

(named for the ship of Charles Darwin's expedition), between Tierra del Fuego and Isla Navarino

Navarino Island () is a Chilean island located between Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego, to the north, and Cape Horn, to the south. The island forms part of the Commune of Cabo de Hornos, the southernmost commune in Chile and in the world, belong ...

, offers a potential, though difficult route. Other passages may be taken around the Wollaston and Hermite Islands to the north of Cape Horn.

All of these, however, are notorious for treacherous ''williwaw

In meteorology, a williwaw (archaic spelling williwau) is a sudden blast of wind descending from a mountainous coast to the sea. The word is of unknown origin, but was earliest used by British seamen in the 19th century. The usage appears for wind ...

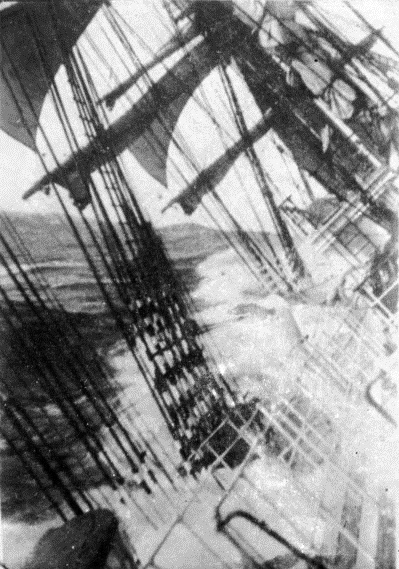

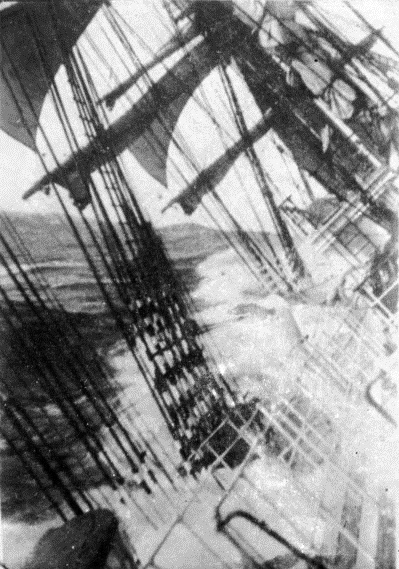

'' winds, which can strike a vessel with little or no warning; given the narrowness of these routes, vessels have a significant risk of being driven onto the rocks. The open waters of the Drake Passage, south of Cape Horn, provide by far the widest route, at about wide; this passage offers ample sea room for maneuvering as winds change, and is the route used by most ships and sailboats, despite the possibility of extreme wave conditions.''Perilous Cape Horn'', by P.J. Gladnick; from eSsortment, 2002. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

"Rounding the Horn"

Visiting Cape Horn can be done on a day trip by helicopter or more arduously by charter power boat or sailboat, or by cruise ship. "Doubling the Horn" is traditionally understood to involve sailing from 50 degrees South on one coast to 50 degrees South on the other coast, the two benchmark latitudes of a Horn run, a considerably more difficult and time-consuming endeavor having a minimum length of .Shipping hazards

Several factors combine to make the passage around Cape Horn one of the most hazardous shipping routes in the world: the fierce sailing conditions prevalent in the Southern Ocean generally; the geography of the passage south of the Horn; and the extreme southern latitude of the Horn, at 56° south. (For comparison,

Several factors combine to make the passage around Cape Horn one of the most hazardous shipping routes in the world: the fierce sailing conditions prevalent in the Southern Ocean generally; the geography of the passage south of the Horn; and the extreme southern latitude of the Horn, at 56° south. (For comparison, Cape Agulhas

Cape Agulhas (; pt, Cabo das Agulhas , "Cape of the Needles") is a rocky headland in Western Cape, South Africa.

It is the geographic southern tip of the African continent and the beginning of the dividing line between the Atlantic and Indian ...

at the southern tip of Africa is at 35° south; Stewart Island/Rakiura

Stewart Island ( mi, Rakiura, ' glowing skies', officially Stewart Island / Rakiura) is New Zealand's third-largest island, located south of the South Island, across the Foveaux Strait. It is a roughly triangular island with a total land ar ...

at the south end of New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

is 47° south; Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

56° north)

The prevailing winds

In meteorology, prevailing wind in a region of the Earth's surface is a surface wind that blows predominantly from a particular direction. The dominant winds are the trends in direction of wind with the highest speed over a particular point on ...

in latitudes below 40° south can blow from west to east around the world almost uninterrupted by land, giving rise to the "roaring forties

The Roaring Forties are strong westerly winds found in the Southern Hemisphere, generally between the latitudes of 40°S and 50°S. The strong west-to-east air currents are caused by the combination of air being displaced from the Equator ...

" and the even more wild "furious fifties" and "screaming sixties". These winds are hazardous enough that ships traveling east would tend to stay in the northern part of the forties (i.e. not far below 40° south latitude); however, rounding Cape Horn requires ships to press south to 56° south latitude, well into the zone of fiercest winds. These winds are exacerbated at the Horn by the funneling effect of the Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

and the Antarctic peninsula, which channel the winds into the relatively narrow Drake Passage.

The strong winds of the Southern Ocean give rise to correspondingly large waves; these waves can attain great height as they roll around the Southern Ocean, free of any interruption from land. At the Horn, however, these waves encounter an area of shallow water to the south of the Horn, which has the effect of making the waves shorter and steeper, greatly increasing the hazard to ships. If the strong eastward current through the Drake Passage encounters an opposing east wind, this can have the effect of further building up the waves. In addition to these "normal" waves, the area west of the Horn is particularly notorious for rogue wave

Rogue waves (also known as freak waves, monster waves, episodic waves, killer waves, extreme waves, and abnormal waves) are unusually large, unpredictable, and suddenly appearing surface waves that can be extremely dangerous to ships, even to lar ...

s, which can attain heights of up to .

The prevailing winds and currents create particular problems for vessels trying to round the Horn against them, i.e. from east to west. This was a particularly serious problem for traditional sailing ships, which could make very little headway against the wind at the best of times; modern sailing boats are significantly more efficient to windward and can more reliably make a westward passage of the Horn, as they do in the ''Global Challenge

The Global Challenge (not to be confused with Global Challenge Award) was a round the world yacht race run by Challenge Business, the company started by Sir Chay Blyth in 1989. It was held every four years, and took a fleet of one-design steel y ...

'' race.

Ice is a hazard to sailors venturing far below 40° south. Although the ice limit dips south around the horn, icebergs

An iceberg is a piece of freshwater ice more than 15 m long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open (salt) water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially-derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". The ...

are a significant hazard for vessels in the area. In the South Pacific in February (summer in Southern Hemisphere), icebergs are generally confined to below 50° south; but in August the iceberg hazard can extend north of 40° south. Even in February, the Horn is well below the latitude of the iceberg limit. These hazards have made the Horn notorious as perhaps the most dangerous ship passage in the world; many ships were wrecked, and many sailors died attempting to round the Cape.

Lighthouses

Twolighthouses

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid, for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Lighthouses mar ...

are located near or in Cape Horn. The one located in the Chilean Navy Station is the more accessible and visited, and is commonly referred to as ''the'Cape Horn lighthouse

. However, the Chilean Navy station, including the lighthouse ( ARLS CHI-030, ) and the memorial, are not located on Cape Horn (which is difficult to access either by land or sea), but on another land point about one mile east-northeast. On Cape Horn proper is a smaller fiberglass light tower, with a focal plane of and a range of about . This is the authentic Cape Horn lighthouse ( ARLS CHI-006, ), and as such the world's southernmost traditional lighthouse. A few minor

aids to navigation

Human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a spectrum of conditions caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a retrovirus. Following initial infection an individual ma ...

are located farther south, including one in the Diego Ramírez Islands

The Diego Ramírez Islands ( es, Islas Diego Ramírez) are a small group of subantarctic islands located in the southernmost extreme of Chile.

History

The islands were first sighted on 12 February 1619 by the Spanish Garcia de Nodal expedition, ...

and several in Antarctica.

Recreational and sport sailing

Despite the opening of the

Despite the opening of the Suez

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same boun ...

and Panama Canals, the Horn remains part of the fastest sailing route around the world, and so the growth in recreational long-distance sailing has brought about a revival of sailing via the Horn. Owing to the remoteness of the location and the hazards there, a rounding of Cape Horn is widely considered to be the yachting equivalent of climbing Mount Everest, and so many sailors seek it for its own sake.

Joshua Slocum was the first single-handed yachtsman to successfully pass this way (in 1895) although in the end, extreme weather forced him to use some of the inshore routes between the channels and islands and it is believed he did not actually pass outside the Horn proper. If one had to go by strict definitions, the first small boat to sail around outside Cape Horn was the Irish yacht

A yacht is a sailing or power vessel used for pleasure, cruising, or racing. There is no standard definition, though the term generally applies to vessels with a cabin intended for overnight use. To be termed a , as opposed to a , such a pleasu ...

''Saoirse'', sailed by Conor O'Brien with three friends, who rounded it during a circumnavigation of the world between 1923 and 1925. In 1934, the Norwegian Al Hansen

Alfred Earl "Al" Hansen (5 October 1927 – 20 June 1995) was an American artist. He was a member of Fluxus, a movement that originated on an artists' collective around George Maciunas.

He was the father of Andy Warhol protégé Bibbe Hans ...

was the first to round Cape Horn single-handed from east to west—the "wrong way"—in his boat ''Mary Jane'', but was subsequently wrecked on the coast of Chile. The first person to successfully circumnavigate the world single-handed via Cape Horn was Argentinian Vito Dumas

Vito Dumas (September 26, 1900 – March 28, 1965) was an Argentine single-handed sailor.

On 27 June 1942, while the world was in the depths of World War II, he set out on a single-handed circumnavigation of the Southern Ocean. He left Buen ...

, who made the voyage in 1942 in his ketch

A ketch is a two- masted sailboat whose mainmast is taller than the mizzen mast (or aft-mast), and whose mizzen mast is stepped forward of the rudder post. The mizzen mast stepped forward of the rudder post is what distinguishes the ketch fr ...

''Lehg II

''Lehg II'' is a ketch that was sailed around the world in 1942 by Argentinian Vito Dumas. The name ''Lehg'' was based on the initials of "four names which marked my life", according to Dumas.

History

Dumas sailed easterly from Buenos Aires, ar ...

''; a number of other sailors have since followed him, including Webb Chiles aboard "" who in December 1975 rounded Cape Horn single-handed. On March 31, 2010, 16-year-old Abby Sunderland became the youngest person to single-handedly sail around Cape Horn in her attempt to circumnavigate the globe. In 1987 The British Cape Horn Expedition, headed by Nigel H. Seymour, rounded Cape Horn in the world's first ever 'sailing kayaks', called 'Kaymaran'; two seagoing kayaks which could link together with two sails mountable in any of the four sailing positions between the two kayaks.

Today, there are several major yacht races held regularly along the old clipper route via Cape Horn. The first of these was the '' Sunday Times Golden Globe Race'', which was a single-handed race; this inspired the present-day '' Around Alone'' race, which circumnavigates with stops, and the ''Vendée Globe

-->

The Vendée Globe is a single-handed (solo) non-stop round the world yacht race. The race was founded by Philippe Jeantot in 1989, and since 1992 has taken place every four years. It is named after the Département of Vendée, in France ...

'', which is non-stop. Both of these are single-handed races, and are held every four years. The ''Volvo Ocean Race

The Ocean Race is a yacht race around the world, held every three or four years since 1973. Originally named the Whitbread Round the World Race after its initiating sponsor, British brewing company Whitbread, in 2001 it became the Volvo Ocean Ra ...

'' is a crewed race with stops which sails the clipper route every four years. Its origins lie in the ''Whitbread Round the World Race

The Ocean Race is a yacht race around the world, held every three or four years since 1973. Originally named the Whitbread Round the World Race after its initiating sponsor, British brewing company Whitbread, in 2001 it became the Volvo Ocean Rac ...

'' first competed in 1973–74. The Jules Verne Trophy

The Jules Verne Trophy is a prize for the fastest circumnavigation of the world by any type of yacht with no restrictions on the size of the crew provided the vessel has registered with the organization and paid an entry fee. A vessel holding th ...

is a prize for the fastest circumnavigation of the world by any type of yacht, with no restrictions on the size of the crew (no assistance, non-stop). Finally, the ''Global Challenge'' race goes around the world the "wrong way", from east to west, which involves rounding Cape Horn against the prevailing winds and currents.

The Horn remains a major hazard for recreational sailors, however. A classic case is that of Miles and Beryl Smeeton

Miles Smeeton (1906-1988) and Beryl Smeeton (1905-1979) were an outstanding couple of travellers, pioneers, explorers, mountaineers, cruising sailors, recipients of numerous sailing awards, farmers, prolific authors, wildlife conservationists an ...

, who attempted to round the Horn in their yacht ''Tzu Hang''. Hit by a rogue wave when approaching the Horn, the boat pitchpoled (i.e. somersaulted end-over-end). They survived, and were able to make repairs in Talcahuano

Talcahuano () (From Mapudungun ''Tralkawenu'', "Thundering Sky") is a port city and commune in the Biobío Region of Chile. It is part of the Greater Concepción conurbation. Talcahuano is located in the south of the Central Zone of Chile.

Geo ...

, Chile, and later attempted the passage again, only to be rolled over and dismasted for a second time by another rogue wave, which again they miraculously survived.

History

Discovery

In 1526 the Spanish vessel the ''San Lesmes'' commanded by

In 1526 the Spanish vessel the ''San Lesmes'' commanded by Francisco de Hoces

Francisco de Hoces (died 1526) was a Spanish sailor who in 1525 joined the Loaísa Expedition to the Spice Islands as commander of the vessel ''San Lesmes''.

In January 1526, the ''San Lesmes'' was blown by a gale southwards from the eastern mo ...

, member of the Loaísa expedition, was blown south by a gale in front of the Atlantic end of Magellan Strait

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural pass ...

and reached Cape Horn, passing through 56° S where ''they thought to see Land's End.'' Since the discovery, the sea separating South America from Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

bears the name of its discoverer in Spanish sources. It appears as ''Mar de Hoces'' (Sea of Hoces) in most Spanish-language maps. In English charts however it is named the Drake Passage

The Drake Passage (referred to as Mar de Hoces Hoces Sea"in Spanish-speaking countries) is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atla ...

.

In September 1578, Sir Francis Drake, in the course of his circumnavigation of the world, passed through the Strait of Magellan into the Pacific Ocean. Before he could continue his voyage north his ships encountered a storm, and were blown well to the south of Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla ...

. The expanse of open water they encountered led Drake to guess that far from being another continent, as previously believed, Tierra del Fuego was an island with open sea to its south. This discovery went unused for some time, as ships continued to use the known passage through the Strait of Magellan.

By the early 17th century the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

was given a monopoly on all Dutch trade via the Straits of Magellan and the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

, the only known routes at the time to the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

. To search for an alternate route and one to the unknown ''Terra Australis'', Isaac Le Maire, a wealthy Amsterdam merchant and Willem Schouten

Willem Cornelisz Schouten ( – 1625) was a Dutch navigator for the Dutch East India Company. He was the first to sail the Cape Horn route to the Pacific Ocean.

Biography

Willem Cornelisz Schouten was born in c. 1567 in Hoorn, Holland, Seve ...

, a ship's master of Hoorn, contributed in equal shares to the enterprise, with additional financial support from merchants of Hoorn. Jacob Le Maire

Jacob Le Maire (c. 1585 – 22 December 1616) was a Dutch mariner who circumnavigated the earth in 1615 and 1616. The strait between Tierra del Fuego and Isla de los Estados was named the Le Maire Strait in his honour, though not without controver ...

, Isaac's son, went on the journey as “chiefe Marchant and principall factor,” in charge of trading aspects of the endeavour. The two ships that departed Holland at the beginning of June 1615 were the ''Eendracht'' of 360 tons with Schouten and Le Maire aboard, and the ''Hoorn'' of 110 tons, of which Schouten's brother Johan was master. It was ''Eendracht'' then, with the crew of the recently wrecked ''Hoorn'' aboard, that passed through the Le Maire Strait

The Le Maire Strait (''Estrecho de le Maire'') (also the Straits Lemaire) is a sea passage between Isla de los Estados and the eastern extremity of the Argentine portion of Tierra del Fuego.

History

Jacob Le Maire and Willem Schouten disc ...

and Schouten and Le Maire made their great discovery:

:“In the evening 25 January 1616 the winde was South West, and that night wee went South with great waves or billowes out of the southwest, and very blew water, whereby wee judged, and held for certaine that ... it was the great South Sea, whereat we were exceeding glad to thinke that wee had discovered a way, which until that time, was unknowne to men, as afterward wee found it to be true.”''The Relation'', pp. 22–23

:“... on 29 January 1616 we saw land againe lying north west and north northwest from us, which was the land that lay South from the straights of Magelan which reacheth Southward, all high hillie lande covered over with snow, ending with a sharpe point which wee called Cape Horne aap Hoorn...”

At the time it was discovered, the Horn was believed to be the southernmost point of Tierra del Fuego; the unpredictable violence of weather and sea conditions in the Drake Passage made exploration difficult, and it was only in 1624 that the Horn was discovered to be an island. It is a telling testament to the difficulty of conditions there that Antarctica, only away across the Drake Passage, was discovered only as recently as 1820, despite the passage having been used as a major shipping route for 200 years.

Historic trade route

From the 18th to the early 20th centuries, Cape Horn was a part of the clipper routes which carried much of the world's trade.

From the 18th to the early 20th centuries, Cape Horn was a part of the clipper routes which carried much of the world's trade. Sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships c ...

s sailed round the Horn carrying wool, grain, and gold from Australia back to Europe; these included the windjammer

A windjammer is a commercial sailing ship with multiple masts that may be square rigged, or fore-and-aft rigged, or a combination of the two. The informal term "windjammer" arose during the transition from the Age of Sail to the Age of Steam ...

s in the heyday of the Great Grain Race of the 1930s. Much trade was carried around the Horn between Europe and the Far East; and trade and passenger ships travelled between the coasts of the United States via the Horn. The Horn exacted a heavy toll from shipping, however, owing to the extremely hazardous combination of conditions there.

The only facilities in the vicinity able to service or supply a ship, or provide medical care, were in the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouzet ...

. The businesses there were so notorious for price-gouging that damaged ships were sometimes abandoned at Port Stanley

Stanley (; also known as Port Stanley) is the capital city of the Falkland Islands. It is located on the island of East Falkland, on a north-facing slope in one of the wettest parts of the islands. At the 2016 census, the city had a popula ...

.

While most companies switched to steamers and later used the Panama canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

, German steel-hulled sailing ships like the Flying P-Liner

The Flying P-Liners were the sailing ships of the German shipping company F. Laeisz of Hamburg.

History

The company was founded in 1824 by Ferdinand Laeisz as a hat manufacturing company. He was quite successful and distributed his hats even ...

s were designed since the 1890s to withstand the weather conditions around the Horn, as they specialized in the South American nitrate trade and later the Australian grain trade. None of them were lost travelling around the Horn, but some, like the mighty '' Preußen'', were victims of collisions in the busy English channel.

Traditionally, a sailor who had rounded the Horn was entitled to wear a gold loop earring—in the left ear, the one which had faced the Horn in a typical eastbound passage—and to dine with one foot on the table; a sailor who had also rounded the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

could place both feet on the table.

One particular historic attempt to round the Horn, that of HMS ''Bounty'' in 1788, has been immortalized in history due to the subsequent Mutiny on the Bounty

The mutiny on the Royal Navy vessel occurred in the South Pacific Ocean on 28 April 1789. Disaffected crewmen, led by acting-Lieutenant Fletcher Christian, seized control of the ship from their captain, Lieutenant William Bligh, and set h ...

. This abortive Horn voyage has been portrayed (with varying historical accuracy) in three major motion pictures about Captain William Bligh

Vice-Admiral William Bligh (9 September 1754 – 7 December 1817) was an officer of the Royal Navy and a colonial administrator. The mutiny on the HMS ''Bounty'' occurred in 1789 when the ship was under his command; after being set adrift i ...

's mission to transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti to Jamaica. The Bounty made only 85 miles of headway in 31 days of east-to-west sailing, before giving up by reversing course and going around Africa. Although the 1984 movie portrayed another decision to go round the Horn as a precipitating factor in the mutiny (this time west-to-east after collecting the breadfruits in the South Pacific), in fact that was never contemplated out of concern for the effect of the low temperatures near the Horn on the plants.

The transcontinental railroads in North America, as well as the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

that opened in 1914 in Central America, led to the gradual decrease in use of the Horn for trade. As steamships

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

replaced sailing ships, Flying P-Liner ''Pamir Pamir may refer to:

Geographical features

* Pamir Mountains, a mountain range in Central Asia

** Pamir-Alay, a mountain system in Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, part of the Pamir Mountains

*A pamir (valley) is a high plateau or valley surro ...

'' became the last commercial sailing ship to round Cape Horn laden with cargo, carrying grain from Port Victoria, Australia, to Falmouth, England, in 1949.

Literature and culture

Cape Horn has been an icon of sailing culture for centuries; it has featured insea shanties

A sea shanty, chantey, or chanty () is a genre of traditional folk song that was once commonly sung as a work song to accompany rhythmical labor aboard large merchant sailing vessels. The term ''shanty'' most accurately refers to a specific ...

and in many books about sailing. One of the classic accounts of a working ship in the age of sail is ''Two Years Before the Mast

''Two Years Before the Mast'' is a memoir by the American author Richard Henry Dana Jr., published in 1840, having been written after a two-year sea voyage from Boston to California on a merchant ship starting in 1834. A film adaptation under the ...

'', by Richard Henry Dana Jr.

Richard Henry Dana Jr. (August 1, 1815 – January 6, 1882) was an American lawyer and politician from Massachusetts, a descendant of a colonial family, who gained renown as the author of the classic American memoir ''Two Years Before the Mast''. ...

, in which the author describes an arduous trip from Boston to California via Cape Horn:

After nine more days of headwinds and unabated storms, Dana reported that his ship, the "Pilgrim" finally cleared the turbulent waters of Cape Horn and turned northwards.

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

, in ''The Voyage of the Beagle'', a journal

A journal, from the Old French ''journal'' (meaning "daily"), may refer to:

*Bullet journal, a method of personal organization

*Diary, a record of what happened over the course of a day or other period

*Daybook, also known as a general journal, a ...

of the five-year expedition upon which he based ''The Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'', described his 1832 encounter with the Horn:

William Jones, writing of his experience in 1905 as a fifteen-year-old apprentice on one of the last commercial sailing ships, noted the contrast between his ship, which would take two months and the lives of three sailors to round the Horn, and birds adapted to the region:

Alan Villiers

Alan John Villiers, DSC (23 September 1903 – 3 March 1982) was a writer, adventurer, photographer and mariner.

Born in Melbourne, Australia, Villiers first went to sea at age 15 and sailed on board traditionally rigged vessels, including ...

, a modern-day expert in traditional sailing ships, wrote many books about traditional sailing, including ''By way of Cape Horn''. More recent sailors have taken on the Horn singly, such as Vito Dumas

Vito Dumas (September 26, 1900 – March 28, 1965) was an Argentine single-handed sailor.

On 27 June 1942, while the world was in the depths of World War II, he set out on a single-handed circumnavigation of the Southern Ocean. He left Buen ...

, who wrote ''Alone Through The Roaring Forties'' based on his round-the-world voyage; or with small crews.

Bernard Moitessier

Bernard Moitessier (April 10, 1925 – June 16, 1994) was a French sailor, most notable for his participation in the 1968 ''Sunday Times'' Golden Globe Race, the first non-stop, singlehanded, round the world yacht race. With the fastest circumn ...

made two significant voyages round the Horn; once with his wife Françoise, described in ''Cape Horn: The Logical Route'', and once single-handed. His book ''The Long Way'' tells the story of this latter voyage, and of a peaceful night-time passage of the Horn: "The little cloud underneath the moon has moved to the right. I look... there it is, so close, less than away and right under the moon. And nothing remains but the sky and the moon playing with the Horn. I look. I can hardly believe it. So small and so huge. A hillock, pale and tender in the moonlight; a colossal rock, hard as diamond."

And John Masefield

John Edward Masefield (; 1 June 1878 – 12 May 1967) was an English poet and writer, and Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate from 1930 until 1967. Among his best known works are the children's novels ''The Midnight Folk'' and ...

wrote: "Cape Horn, that tramples beauty into wreck / And crumples steel and smites the strong man dumb."

A memorial presented in Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy and a scientist. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, FitzRoy's second expedition to Tierra de ...

's bicentenary (2005) commemorates his landing on Cape Horn on 19 April 1830.

Canadian singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot

Gordon Meredith Lightfoot Jr. (born November 17, 1938) is a Canadian singer-songwriter and guitarist who achieved international success in folk, folk-rock, and country music. He is credited with helping to define the folk-pop sound of the 1960 ...

wrote a song entitled "Ghosts of Cape Horn".

In 1980 Keith F. Critchlow directed and produced the documentary film

A documentary film or documentary is a non-fictional film, motion-picture intended to "document reality, primarily for the purposes of instruction, education or maintaining a Recorded history, historical record". Bill Nichols (film critic), Bil ...

"Ghosts of Cape Horn", with the participation and archaeological consulting of famous underwater archaeologist Peter Throckmorton

Edgerton Alvord Throckmorton (July 30, 1928 – June 5, 1990), known as Peter Throckmorton, was an American photojournalist and a pioneer underwater archaeologist. Throckmorton was a founding member of the Sea Research Society and served on its Bo ...

.

Further reading

* ''Around Cape Horn: A Maritime Artist/Historian's Account of His 1892 Voyage'', by Charles G. Davis and Neal Parker. Down East Books, 2004. * ''Cape Horn. A Maritime History'', by Robin Knox-Johnston. London Hodder&Stoughton * ''Cape Horn: The Story of the Cape Horn Region'', by Felix Riesenberg and William A. Briesemeister. Ox Bow Press, 1994. * ''Cape Horn and Other Stories From the End of the World'', by Francisco Coloane. Latin American Literary Review Press, 2003. * ''Gipsy Moth Circles the World'', Sir Francis Chichester; International Marine, 2001. * ''Haul Away! Teambuilding Lessons from a Voyage around Cape Horn'', by Rob Duncan. Authorhouse, 2005. * ''Rounding the Horn: Being the Story of Williwaws and Windjammers, Drake, Darwin, Murdered Missionaries and Naked Natives – A Deck's-Eye View of Cape Horn'', by Dallas Murphy. Basic Books, 2004. * ''En el Mar Austral'', by Fray Mocho. University of Buenos Aires Press (La Serie del Siglo y Medio), 1960. An incredible account of the southern tip of South American by an Argentine Journalist. * ''High Endeavours'', by Miles Clark. Greystone, 2002. An account of the lives of the author's god-father Miles Smeeton, and his wife Beryl, including a couple of spectacular trips to the Horn. * '' A world of my Own'' by Robin Knox-Johnston. An account of the first solo non-stop circumnavigation of the world via Cape Horn between 1968 and 1969. * ''Expediciones españolas al Estrecho de Magallanes y Tierra de fuego'', by Javier Oyarzun. Madrid: Ediciones Cultura Hispánica . * ''Storm Passage'' by Webb Chiles. Times Books * ''The Last of the Cape Horners. Firsthand Accounts from the Final Days of the Commercial Tall Ships'', edited by Spencer Apollonio. Washington, D.C.: Brassey's, Inc. 2000. *''The Cape Horn Breed'', by William H.S. Jones, 1956 *''The Log of a Limejuicer'', by James P. Barker, 1933See also

* affecting the nearbyPicton, Lennox and Nueva

__NOTOC__

Picton, Lennox and Nueva () form a group of three islands (and their islets) at the extreme southern tip of South America, in the Chilean commune of Cabo de Hornos in Antártica Chilena Province, Magallanes and Antártica Chilena Reg ...

islands

*

*

* , the Australian landmark on the clipper route

*

* , the second passing around Cape Horn

*

* Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

* Great capes

In sailing, the great capes are three major capes of the continents in the Southern Ocean—Africa's Cape of Good Hope, Australia's Cape Leeuwin, and South America's Cape Horn.

Sailing

The traditional clipper route followed the winds of the ...

References

* The War with Cape Horn, by Alan Villiers. Published by Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971.External links

Guide: How to visit Cape Horn

International Association of Cape Horners

Chilean Brotherhood of Cape Horn Captains (Caphorniers)

– Chilean sculptor José Balcells' article (Spanish)

Robert FitzRoy's commemorative plaque in Horn Island (image)

– antique charts of the Cape Horn region

–

Ellen MacArthur

Dame Ellen Patricia MacArthur (born 8 July 1976) is a retired English sailor, from Whatstandwell near Matlock in Derbyshire, now based in Cowes, Isle of Wight.

MacArthur is a successful solo long-distance yachtswoman. On 7 February 2005, ...

's rendezvous at Cabo de Hornos

Satellite image and infopoints

on BlooSee {{Authority control Extreme points of Earth Landforms of Magallanes Region

Horn

Horn most often refers to:

*Horn (acoustic), a conical or bell shaped aperture used to guide sound

** Horn (instrument), collective name for tube-shaped wind musical instruments

*Horn (anatomy), a pointed, bony projection on the head of various ...

Landforms of Tierra del Fuego

Cliffs of Chile

Maritime history of the Dutch Republic

1616 in the Dutch Empire